by acackler | Aug 23, 2021 | General

Okay okay, I know. I’ve only released one short story, so what kind of an authority am I? Well, I’m not. I’ll admit that right up front. In this particular format, I’m kind of learning as I go. I mean, I took classes in it back in college. I...

by acackler | Jul 3, 2021 | General, The Little Owl

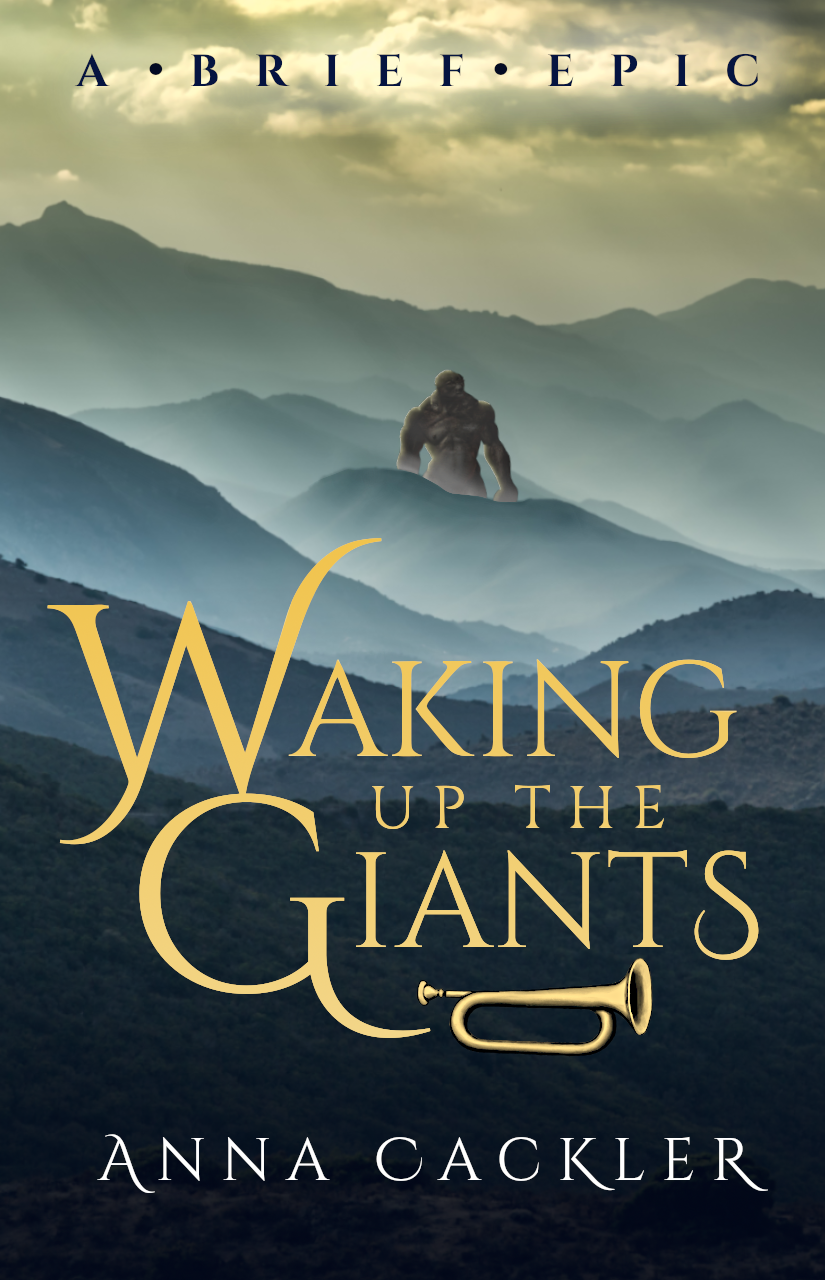

I am so excited to announce that my latest short story is available now! Waking Up the Giants is one of those niggling little stories that started out one way… and of course became something entirely new and amazing that I would have NEVER predicted. This story...